SCARECROW AMONG THE CHANCELLORS

an installation for

'Bodies in Translation: Age and Creativity' at Mount St. Vincent University Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia

9 September - 12 November 2017

http://www.msvu.ca/en/home/research/centresandinstitutes/centreonaging/25thanniversaryeventsandactivities/artexhibition.aspx

http://www.cbc.ca/arts/everyone-is-temporarily-able-bodied-this-halifax-exhibit-brings-together-aging-and-disability-1.4368983

audio description from the exhibition Bodies in Translation: Activist Art, Technology, and Access to Life at Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery:

http://bit.mat3rial.com/node/onni-nordman/

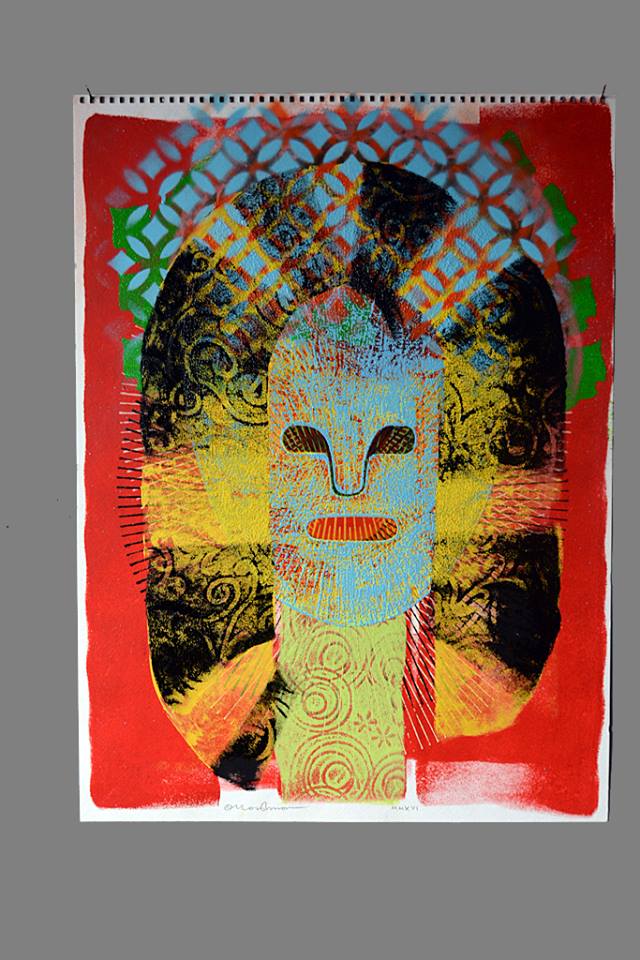

Scarecrow Among the Chancellors stations a weathered survivor before a monument of top dogs. The monotyped faces on the wall are derived from a 1967 book, Swiridoff: Portraits of German Political and Economic Life, of photographs of mid-century politicians and business figures of the postwar economic miracle —Wirtschaftswunder—era. These are the faces of some of the most profoundly focused and accomplished adults in the public sphere of their time. The service-staff working stiff scarecrow is experiencing a moment of status vertigo, uncertain whether his life has borne sufficient fruit in comparison. This is expressed in the manner of the scientist Wile E. Coyote, who, having stepped off a cliff, saunters blithely on until he becomes aware of his circumstance, at which point he articulates his dread as the law of falling bodies reasserts itself.

Has one grown old without growing up? For artists, as for everyone, each instant of one's life is a moral minefield that turns us either into Isaiah Berlin's hedgehogs, who view the world through the lens of a single defining idea, or foxes, who draw on a wide variety of experiences and for whom the world cannot be boiled down to a single idea. For me art's first relevance is its heuristic value— I always want the work to be a little smarter than I am. To invent and construct ideas in concrete form is also a way of constructing one's self. The promise of a lifetime's labour is the hope of a 'late style': that is, an unprecedented, personal voice. Titian, in his late paintings, used as little paint as is humanly possible to conjure a felt reality. Beethoven, in his last piano sonata, No.32, Op. 111, effectively anticipates boogie-woogie jazz in 1822. At some point in an artist's life, perhaps one has prepared oneself by giving to art, in the form of work and thought, sufficiently that one can now take from art ideas and forms which are beyond one's grasp.

Has one grown old without growing up? For artists, as for everyone, each instant of one's life is a moral minefield that turns us either into Isaiah Berlin's hedgehogs, who view the world through the lens of a single defining idea, or foxes, who draw on a wide variety of experiences and for whom the world cannot be boiled down to a single idea. For me art's first relevance is its heuristic value— I always want the work to be a little smarter than I am. To invent and construct ideas in concrete form is also a way of constructing one's self. The promise of a lifetime's labour is the hope of a 'late style': that is, an unprecedented, personal voice. Titian, in his late paintings, used as little paint as is humanly possible to conjure a felt reality. Beethoven, in his last piano sonata, No.32, Op. 111, effectively anticipates boogie-woogie jazz in 1822. At some point in an artist's life, perhaps one has prepared oneself by giving to art, in the form of work and thought, sufficiently that one can now take from art ideas and forms which are beyond one's grasp.

The Scarecrow as doorman security guard.

MSVU Art Gallery technician David Dahms. Thanks, David!

Burdock Scarecrow

SCARECROW AMONG THE CHANCELLORS

(2017) Draped burdock sculpture with 80 monotypes. Sculpture 2 m, Monotypes 3 x 3 m

in situ at exhibition 'Bodies in Translation', Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery

September-November 2017 (photo by Steve Farmer)

Ten of the eighty 'Chancellor' monotypes

SCARECROW AMONG THE CHANCELLORS

BURDOCK

Burdock, family Arctium, with its homely leaves and pesky seeds, used to be a vexing urban weed before it all but disappeared from everywhere but wastelands over the last twenty or thirty years. Like many alleged weeds it has no end of profitable uses.

Burdock flowers provide essential pollen and nectar for honeybees around August when clover is on the wane and before the goldenrod starts to bloom. Burdock's clinging properties, in addition to providing an excellent mechanism for seed dispersal, led to the invention of the hook and loop fastener, or Velcro. Burning the plant when green produces a large amount of carbonate of potash.

Burdock is a popular root vegetable in Asia and around the Pacific. The immature flower stalks and spring leaves are also eaten. Burdock is a staple of folk herbalism and Chinese traditional medicine, considered one of nature's best blood purifiers. In the macrobiotic diet, it is considered especially yang, or the positive/active/male principle in nature. But in magical traditions, burdock is associated with feminine energies, Venus, and the element of water. The root can be carved into a figure, dried and carried or worn as an amulet.

The Burryman or Burry Man is the central figure -- a local man is covered from head to ankles in burrs-- who parades in an annual ceremony or ritual on the second Friday of each August for nine hours or more around a seven-mile route through South Queensferry near Edinburgh. It has been suggested that he carries on a tradition thousands of years old; that he is a symbol of rebirth, regeneration and fertility (similar to the Green Man) that pre-dates almost all contemporary religions; or that he is a "scapegoat" and may even originally have been a sacrificial victim.

I discovered all this just about two years ago. My own burrymen go back to 1987.

The Queensferry Burryman: www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDvd4Efy3n8

BURR MEN

Burr, sticky-burr, buzzy, beggar's button. The brown seedpod artlessly epitomizes the completed, consummated, crepuscular stage of a cycle.

My first burr man. 'Hero', was in the group show Ecphore 1987 in the long-gone Bryant Building in downtown Halifax. I wrote in the catalogue:

"I've always loved the works of the relatively short-lived mode of Arte Povera. My 'Hero' is an appreciation of the beautiful fingers moonward of Merz, Kounellis, and others.

Imagine an artist of the past, of the 18th or the 14th century, with an oeuvre of burdock sculptures: a full-sized caricature of a landlord, set upon his land to overrun his barley field with rank weeds seeded from his own image; or a colossal corn goddess set aflame at harvest moon.

Such works surely had their making and their life, but I've never seen them mentioned in art or folk history. The idea is so obvious and the material so ubiquitous that it must have a trail and a tale."

The second burr man, 'Founder', was shown at AGNS in the show 'Industrial Strength' in 1999. Later I gave it to my daughter who put it on her lawn where it was destroyed during Hurricane Juan in 2003. This material is resilient.

The third burr man, 'Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres, Nude, at the Age of 102', was made for Lumière 2011, Sydney's annual night-time art festival. It was a salute to the cast-lead public statue of the city's founder, who actually lived to the age of 102, (1721 - 1824). Later it found a home in the botanical sculpture garden at the Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens.

The fourth, the full-figure 'Babysitter', was for Lumière 2012. 'Scarecrow' is the fifth figurative burr man. There have been other experiments,

including some in a show, 'XPRXXCODX', at Cape Breton Centre for Craft and Design in 2015, of functioning QR codes made of burdocks and other materials.

SCARECROW

Taking into account the title, Scarecrow Among the Chancellors, the immediate common sense reading of the characters would be that the burr man is obviously the scarecrow, so the chancellors must therefore be the crows. But no responsible crow or raven has been fooled by scarecrows for centuries, if ever.

So it is just as likely that the chancellors are the farmers, bureaucratically maintaining security arrangements and keeping the scarecrow in a job regardless of effectiveness. The scarecrow is a security worker --a subset of soldier-- whose life and opportunities are subsidized and underwritten by the state.

The pilferage of the crows may indeed reside exclusively within the ranks of both labour and management as part of the cost of doing business, and be written off as acceptable loss or 'shrinkage'. The scarecrow, like much visible security, is mostly performative.

The burr man is modelled as an allusion to the figure of Leviathan in Abraham Bosse's etching for the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' 1651 book, depicting the colossal figure of absolute power composed of the multitudes of the commonwealth, facing inward toward the centre or sovereign authority.

The manuscript created for Charles II contained an alternate drawing by Bosse in which the body is composed of faces looking outward, a reminder of the obligations of power.

The burrs of the scarecrow point inward. The scarecrow contains multitudes homogenized into a labour pool. This individual who emerges temporarily, Arcimboldo-like, is a toughened factotum, drudging to survive. Here his name is Max Klinger. After work, his efforts go to composing a string quartet, his sixteenth, all resting in a drawer unperformed. He reads the news from both left and right positions, and takes pride in his acumen. He follows the affairs of the chancellors and allows himself few presumptive opinions. He approves of bureaucracies based on rational-legal authority. He also is convinced that the customer is king. The is the best job he can get at his age. He has a lifetime's with of practical know-how but this has his limits: He obliviously wears his budget gold necklace chain to work. This does not discourage crows.

In time he inevitably morphs into another interchangeable member of the mass, with different characteristics but the same uses.

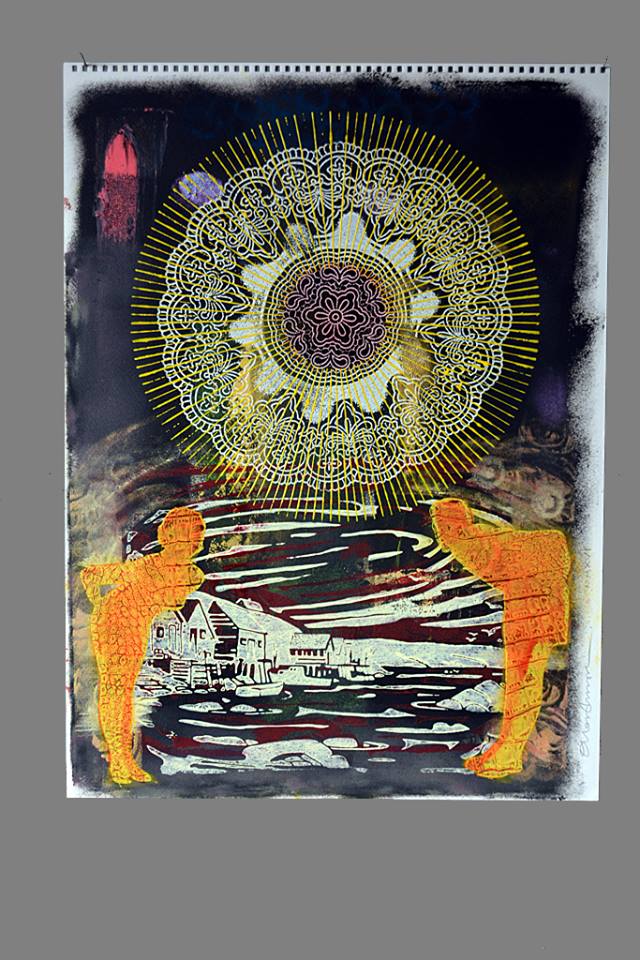

MONOTYPE

The monotype painting on its initial matrix is always ceded to the contingent effects of the transfer process. When the wet paint image is pressed to its support, the image that results always emerges from a zone of chance, pressure, and fluid dynamics. You can plan it only so far. The most interesting results come from pressing the paper with the hands and arms (Degas sat on his) instead of running it through a press or mangle. The image, which is best rendered with no great fastidiousness, yields an organic singularity. It becomes better than what you drew.

In his 'Salon of 1859' Baudelaire wrote, apropos of Delacroix, Manet, et al, of the new distance at which modern painting (as opposed to Salon painting) needed to be seen. This was a distance too great for the subject to be analyzed or even understood, but which, when seen through "the thick and transparent varnish of the atmosphere" snapped into place through optical blending into an energy which suggests the feeling of actual space, of a living presence seen across a room. The notion was that a painting done in broad strokes in frank colours captures a space that functions as a real space; that we can enter it, experience its environment. Close up, it is a discoloured, softened, illusory space. Seen from a short distance, in the small amount of air finding room between the painting and the observer's eye, there flows all the energy of actual space. Monotype contains this effect in its very nature-- blots come to life.

In monotyping's method is a metaphor: there is the zone of intention, the zone of encounter, and the zone of consequence. The initial painting can be exacting, or it can be a snarl. It scarcely matters. When it is transferred to the support other forces dispose.

In life one prepares a face to meet the faces that you meet, but on the night one will be read by others in a hundred fractured impressions, few of which may be entirely flattering. You step out into the world escorting confidently your sense of self to discover that you end up a detail of phenomenality, smeared onto the world, possibly a stranger to yourself and more cogent because of it. Aging feels like this.

CHANCELLORS

The silverbacks, apex predators, and grey eminences in this directorate or camarilla are often as not born on third base, but few are foolish enough to believe that have hit a home run because of it. This is near enough to a meritocracy. They are arrayed in the reputable postures of ceremonialist portraiture. They bear the leprose hydroid texture of transferred oil paint. If, as de Kooning said, flesh was the reason paint was invented, then geriatric flesh is why the monotype steps up to punch the clock.

This veteran power elite are the few who minister the many. Unlike the scarecrow mass-presence they possess the prerogative of individual recognition. This, though, is at the price of a greater deliberate subsumption to the collective flow. To stay in the swim they are compelled to be constantly and actively pressed and stamped onto the public world. The cost of this is that one comes to rely on a persona, a prosthetic self. Where self-identity was once assumed to be a possession of the individual, in their societal roles these public selves are reorganized relentlessly into an abstract property subject to endless processes of accommodation and stipulation. To be a fox or a hedgehog takes on great urgency when operating on a (golden) chain gang.

The test of aging might be whether one is in the driver's seat or the passenger seat of one's life.